I would like to make a land acknowledgement to recognize and acknowledge the Indigenous people of the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania land: the Shawnee (shaw-nee) and the Osage (ow·seij). I am living and creating art on Jö:deogë’ (joan-day-o-gan’t), a Senaca (seh·nuh·kuh) word for Pittsburgh or “between two rivers.” While a land acknowledgement is not enough, it is an important step for social justice that allows us to promote Native and Indigenous peoples and their cultures. Let this land acknowledgement be an opening for those who read it to contemplate how to help the Indigenous movements for sovereignty and self-determination.

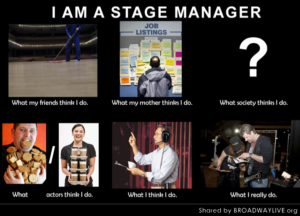

A stage manager is a lot of things: a nurse, a therapist, a personal assistant. They work long hours to ensure that the show is at the best it can be, and once the show is open, the integrity of it stays in place. Stage Managers are expected to be the first ones to arrive and the last ones to leave, and if there is a problem, they are the first ones sought out to fix it. There is a lot of pressure put on them to make sure everything runs smoothly, but they are not allowed to have an artistic opinion. An unspoken rule, stage managers are expected to sacrifice their personal time when a show is in rehearsal/shows. Their phone is always on, and any phone call is expected to be answered. It is a thankless job, but one of the most important when it comes to theater. So, how does it work if a stage manager is fighting a mental illness? The answer: very carefully.

My name is Madison, and I am a master’s student at Carnegie Mellon University and am interning at Davis Shakespeare Festival. I have been stage managing for six years and have been battling major depressive disorder since I was in middle school. Just like most invisible illnesses, some days are better than others. Some days I can take blocking, keep up the rehearsal report, engage with the actors, joke with the director, and keep an eye on the assistant stage manager’s progress on the prop map. Other days, it’s all I can do to make sure everyone has signed in on time. However, there is no such thing as a “mental health day” in my theater world. Stage managers are expected to be present no matter what. During my freshman year of undergrad, one of my professors said to me, “If you are throwing up, sit in the back with a bucket.” So, the culture of taking care of one’s self first is low to nonexistent.

Being a stage manager with depression has been difficult because even though I am in rehearsal all evening and weekend, there are still things that are required of me that take outside time to accomplish. However, there are days when I can’t even get out of bed. There have many times when I have to spend the entire day mentally preparing myself to go to rehearsal; I don’t shower, or brush my teeth or hair, and most of the time I show up in the clothes I wore the day before because they were easily accessible (i.e. they were laying on my floor). That means I did not have the chance to accomplish the paperwork that needed to be done, or to upload the blocking videos that were taken last week, or to e-mail the cast last evening’s notes. And when the director is looking for a reason as to why I haven’t accomplished anything, “Because my depression kept me in bed all day” isn’t an answer they will accept.

So, how do I manage? Well to begin with, I make the most of the breaks I did get. It took me a couple of years, but I finally started putting my foot down and not allowing anyone to talk to me about the show during the allotted 10-minute breaks that we get every hour and a half. Also, I always physically leave the room and allow myself to breathe and let go of the stress that has been accumulating. There is another unspoken rule that stage managers should work through those breaks, to keep the process running smoothly when the break is over. But I believe that rule is another cultural norm that was imbedded in my theatre circles, but perhaps not everywhere. I am actively working against it, so those who come in after me can see that taking that break is necessary. In addition to stepping out of the room, I also try to have a real, genuine conversation with someone. Sometimes it is an actor or a person who is also part of the rehearsal process, but I might need a break from the whole entity and will make a phone call. This has taken some pushing on my part, because depression sucks away energy, and it is extremely difficult to start a conversation when sitting by yourself is easier. But once I get over the initial hump, I often find myself grateful for the interaction.

Depression is a tricky illness. It has become normalized in pop culture, but almost too much so. It seems that people have a specific idea of what depression looks like, so when it manifests in different ways or in ways that aren’t “romantic,” suddenly it isn’t legitimate anymore. My depression keeps me in bed. It makes me so drained that I can barely talk to anyone and has kept me from being able to do my work at times. But I am learning to cope, and I am gaining skills to try and prevent frequent episodes. I love theatre, and I love stage managing. I won’t let my mental illness stop me from doing what I love.

So long and thanks for all the fish,

Madison E. Morrow

She/Her/Hers

Davis Shakespeare Festival Digital Internship Participant

Carnegie Mellon University

Master of Arts Management 2022