I would like to acknowledge that the land I am writing from is the unceded land of the Wampanoag and Massachusett tribes. With this knowledge of the Indigenous origins of this land, and in acknowledgement of the painful history of our predecessors, I recognize the Wampanoag and Massachusett people and their elders, past and present, as the original caretakers of this land, as well as the history of violence and forced removal on this land.

When interviewing for the DSF Digital Internship Program, we were asked to create a presentation on a theatrical topic of interest to us, and I spent days racking my brain for a presentation idea “good enough” for this program, one that could “make up” for all the things I thought undesirable – in particular, the name of the school on my resume. I’m a student at a state school where the theatre department is somewhere around 200 people. The most common response when I tell people what I’m studying is something along the lines of, “wait, they do that there?” The students and faculty here are some of the greatest artists I’ve had the privilege of knowing, and adore the community I have here, but I won’t pretend I came here because I desperately wanted to be in this program – this was just what I could afford.

When it came to applying for internship programs before DSF, I spent a lot of time trying to make the case for the quality of my education in rooms full of people from recognizable private universities. I seldom see people from my university or the system it belongs to represented in professional theatre staff or artists, despite knowing firsthand their talents. I’ve seen friends and peers asked to explain why BSU (Bridgewater State) is just as good as NYU to employers from theatre companies who tout their commitment to anti-classism and financial accessibility for their audiences. Theatres have committed themselves to financial accessibility in an incredible way, potentially cultivating a new generation of young artists who want to study theatre or pursue it professionally – but will they be met with the same commitment to accessibility as their audiences when that time comes?

In 2019, Playbill published an article listing the alma maters of the Tony Award nominees in all categories. Of 123 nominees, 115 (or 94.3%) were college-educated, and of that 115, 106 (or 86.2%) went to private colleges or universities. Each year, OnStage Blog releases a ranking of their top collegiate theatre programs, and of their 2020 Top 30 Schools, 23 (or 73.6%) were private universities, and all 30 schools required some sort of on-campus audition or interview, with no school’s websites detailing any accommodations or assistance with travel or housing expenses. In my own experience applying to schools, it was simply not realistic for me to take out additional travel and housing expenses and time off from school just for an uncertain chance at admission to an already expensive college – which unfortunately eliminated most of what I was told were “good theatre schools” as options for me.

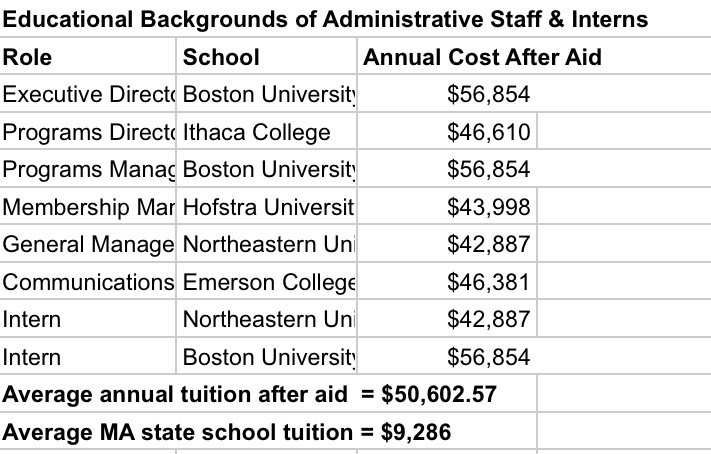

In some of my own research into a local theatre company’s staff educational backgrounds, I found that every single staff member attended a private college or university, with an average cost of $50,602.57 – over five times higher than the average tuition of a state school in the same state. I’ve kept the name private so as to not make anybody feel targeted, but this is a company locally known for anti-classism and accessibility initiatives – and yet, the standard for employment with them seems to be a widely financially inaccessible education.

As theatre artists, administrators and employers, we must examine where those individuals we seek to make our work accessible to have been left out of our creative spaces. When we commit to audience accessibility, but the resources we provide for young artists establish objective “best schools” that are financially out of reach for them, we may have then communicated that they are allowed to see the art, but are not good enough to make it. Why do we think certain institutions produce better artists, and why are those institutions so often the most expensive or selective? Why do we believe it is appropriate to gauge the talent or potential of an individual based on something so closely tied to economic privilege?

This post is not meant to dismiss the accomplishments of those artists privileged enough to attend certain schools, but rather, to acknowledge that talent and passion have no alma mater or economic status. When we commit to financial accessibility for our audiences, we must also extend that commitment to our artists.

Sources

https://www.playbill.com/article/schools-of-the-stars-where-the-2019-tony-nominees-went-to-college

https://www.onstageblog.com/editorials/2019/10/1/top-acting-schools-2019-20

Kyle Imbeau (he/they)

DSF Internship Participant

Bridgewater State University

B.A. Theatre Arts, 2023